1. Generation Systems: The Foundation of Supply

The energy ecosystem begins with generation: the conversion of primary energy sources into electricity. Canada’s generation mix is one of the most diverse in the world, dominated by hydropower but also featuring significant contributions from nuclear, natural gas, wind, solar, and coal. Each province's mix is unique, shaped by its natural resource endowments and policy choices.

- Hydropower: The backbone of the system, particularly in Quebec, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Large-scale hydro provides a reliable, low-carbon source of baseload power.

- Nuclear Power: Concentrated in Ontario, nuclear power provides a significant share of the province's baseload electricity with zero greenhouse gas emissions. Refurbishment and life-extension projects are critical to maintaining this capacity.

- Fossil Fuels: Natural gas plays a crucial role as a flexible generation source, able to ramp up and down quickly to balance fluctuations from renewable sources. Coal is being phased out across the country.

- Renewable Energy: Wind and solar power are the fastest-growing segments of the generation mix, driven by declining costs and climate policy. Their intermittency, however, presents a significant challenge for grid operators.

2. Transmission Systems: The Arteries of the Grid

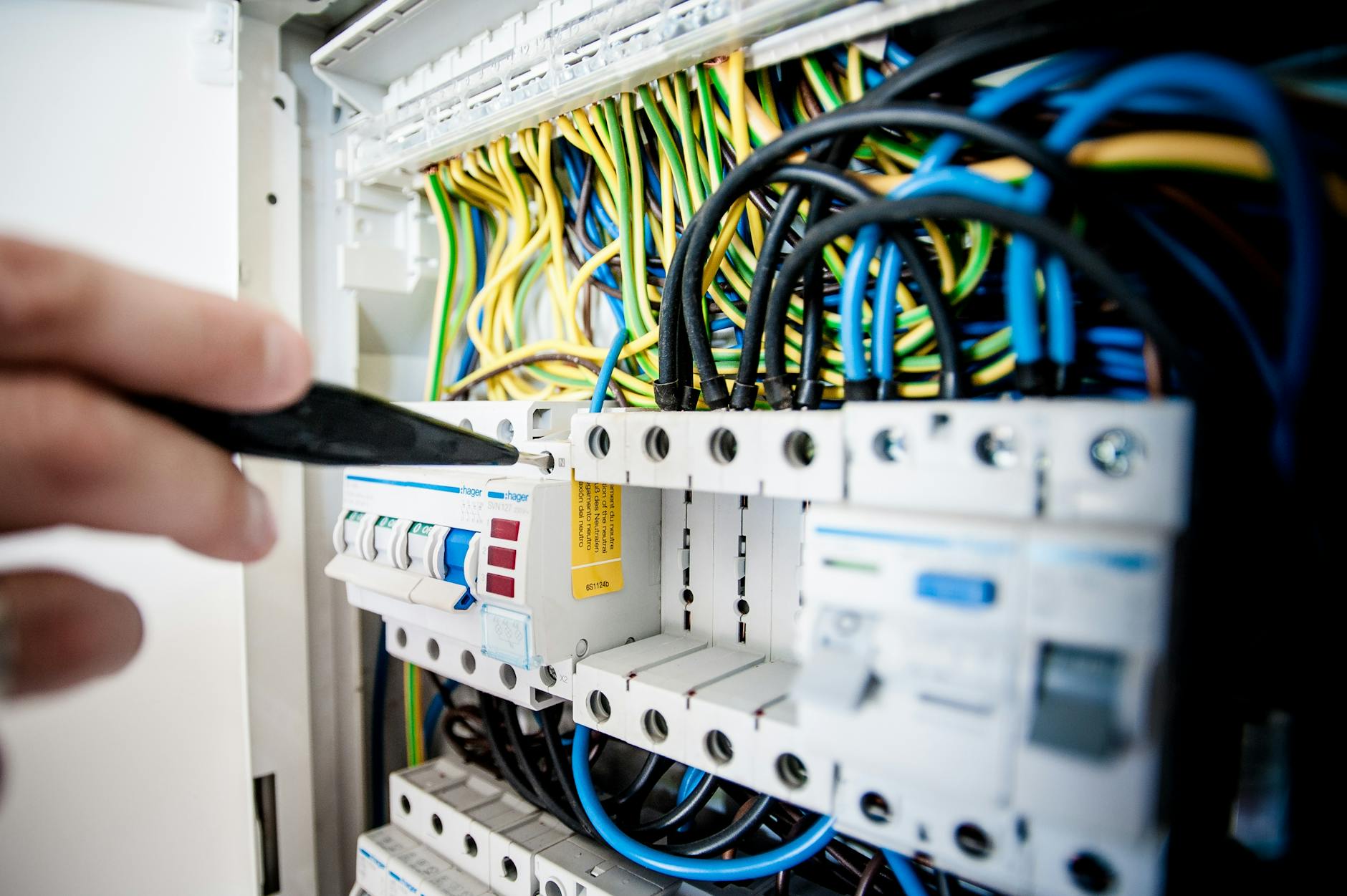

Once generated, electricity must be transported over long distances from power plants to population centers. This is the role of the high-voltage transmission system, a vast network of power lines and substations that function as the arteries of the grid. In Canada, these systems are typically owned and operated by provincially-owned Crown corporations or regulated private utilities.

The transmission network is critical for reliability, allowing power to be redirected in the event of a local plant failure or transmission line outage. It also enables electricity trade between provinces and with the United States, which can enhance economic efficiency and grid stability. Building new transmission infrastructure, however, is a long, complex, and often contentious process, involving significant capital investment and extensive regulatory and public consultation.

3. Grid Operations and Control Centers: The Brains of the System

The moment-to-moment management of the electricity grid is handled by system operators from sophisticated control centers. These operators, often organized as Independent System Operators (ISOs) or as part of vertically integrated utilities, have one primary mission: to balance electricity supply and demand in real time, every second of every day. A failure to do so can lead to grid instability and, in the worst case, widespread blackouts.

Control centers are the nerve centers of the grid. Using advanced software and communication systems, operators monitor grid conditions, dispatch power plants, and manage electricity flows across the transmission network. They are responsible for forecasting electricity demand, scheduling generation, and managing the wholesale electricity market where it exists.

The job of a system operator has become exponentially more complex with the rise of intermittent renewable energy. They must now manage a system where a significant portion of the supply can fluctuate unpredictably with the wind and sun, requiring more sophisticated forecasting tools and faster-acting resources to maintain balance.

4. Digital Layers: Monitoring, Forecasting, and Coordination

Underpinning the entire modern energy ecosystem is a growing digital layer of sensors, communications networks, and data analytics platforms. This digital infrastructure is essential for the visibility and control needed to manage a complex, dynamic grid.

Simplified Structural Diagram of the Energy Ecosystem (Non-Financial)

[ Generation Sources (Hydro, Nuclear, Gas, Renewables) ]

↓

[ High-Voltage Transmission Network ]

↓

[ Distribution System (Local Utilities) ] ←→ [ Digital Layer (ISOs, Control Centers) ]

↓

[ End Users (Industrial, Commercial, Residential) ]

Key components of this digital layer include:

- Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA): Systems that allow operators to remotely monitor and control equipment across the grid.

- Energy Management Systems (EMS): Advanced software applications used in control centers for grid optimization and reliability management.

- Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI): Smart meters that provide real-time data on electricity consumption and enable demand-response programs.

- Synchrophasors: High-speed sensors that provide a granular, real-time view of grid stability, allowing for the early detection of potential problems.

This digital layer is not just an add-on; it is becoming the central nervous system of the grid, enabling the coordination and intelligence required to manage a 21st-century energy system. However, it also introduces new vulnerabilities, particularly around cybersecurity, which has become a top priority for operators and regulators.